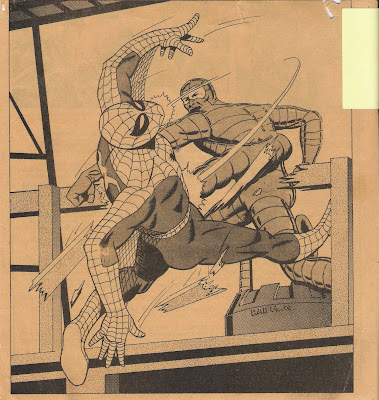

Had he been a piano man he would have written differently, of course, about the things that stirred him. High on the list would have been the sense of wonder – that life was an adventure waiting to be lived. He also had a sentimental streak and would sing along to Harry Chapin (it was always funny to hear his deep speaking voice give way to his falsetto singing). He devoured fantasy and science fiction, mostly through visual means: movies and comics. He was an artist himself:

He had hoped to be able to work in the comics industry, but never broke in. When he drew that for a local comic shop’s newsletter, it was early 1980, and he was a married man with a 7-year old: me. His adventure was trying to save up enough to move us out of my grandmother’s house and into a home of our own, and to that end he drove a delivery truck all over Long Island, New York City, and into New Jersey. He would then work nights as a pack-out clerk at Pathmark. Mom worked as a bookkeeper to handle everyday bills.

This didn’t leave a lot of spare time for traditional family activity, so he made do. During the summer he would take me along on his delivery runs, sort of a prototype take-your-kid-to-work-day. In those days nobody worried enough to tell Dad to stop bringing me, and I enjoyed it enough to want to help bring in the smaller boxes whenever Dad made a stop. Then we’d head over to White Castle and compete to see who could down a burger in the fewest bites.

It was about that time that I first remember learning that Dad was, in fact, my stepfather: he’d married Mom before I was two and promptly adopted me, my sire ceding his parental rights to concentrate on the family he was starting with his second wife. That was just things. It was factual, sort of a family trivia question: “Despite being the eldest son, it is his younger brother who is ‘Junior,’ and not this obscure blogger.” Otherwise it was unimportant; certainly it made no difference to him that I ever saw, or in how he treated my brother and sister when they arrived.

We did get that home he’d helped to scrimp and save for: a handyman’s special that was only livable after months of hard work – none of it contracted. My father was incredibly handy. I think that house alone forestalled the eventual demise of Rickel’s Home Center for a year. He rebuilt walls, worked on the roof, did shingling, and worked nights anyway, though he cut back on the day job. No more truck trips to the City from our Suffolk County home.

Another of my Dad's dreams came true when my parents opened a screen-printing shop. For a few years my father was as happy as I can remember. He didn’t need to work nights anymore. He was finally using his artwork and creativity every day. Unfortunately business dried up and the shop failed after a couple of years; without complaint, Dad went right back to the daily grind (and sometimes nightly as well), even as we moved off Long Island and down to New Jersey. He still had his own home and family, above all else.

He taught me chess. He taught me to catch and throw. Better, he taught me about forgiveness and responsibility. He’d promised to take me to see Raiders of the Lost Ark when it debuted, as long as I did well on my weekly progress report at school. We were rated from 0-4 in five categories.

I got a six - total. Dad shook his head, signed the report, and put it back in my bookbag. (Mom always signed the 19s and 20s; Dad got called in if I dropped to 12 or so.) Then he said, “Well – get your coat.” I lost other privileges, but we got to see the movie, father and son.

Not to say that he was lax when it came to us misbehaving. It was a bad idea to be ill-mannered, or lippy with my elders - and "Heaven help you if you ever bring a cop to my door." Most kids blow off that sort of thing as they go stupid in puberty, but this all sank in because of something that happened when I was fifteen. My father decided that a largish tree had to come down in our yard to keep from damaging the garage. At the last moment, something happened and the tree did not come down alongside the house, as he hoped, but across and into the neighbor’s yard – the neighbors we’d never gotten along with from the day we arrived in New Jersey the year before. From the other side of their crushed fence floated the lament – “Oh, that’s just GREAT, sir.”

Dad had a pretty good temper when he needed it, but all he said was, “I’m sorry. I'll make it right.” And after getting the tree sawed into hunks and out of the way, he paid for the replacement.

We played board games and watched the new Star Trek and I got to be his main assistant as he installed the above-ground pool we got when I was in high school. As I got older and it became obvious that I enjoyed writing, he talked about doing an independent comic – my words appearing over his artwork – but I should finish college first, just in case. In the meantime, I worked after school, biking miles each way since we had exactly one car, always in use. My folks felt that it was good for me to learn to budget in the time for the trip, to take it on myself to get to and from the job, unless it was raining.

During this time, my relationship with Dad really began to change. Without losing any of the respect I had for him, I began to gain a different status, a friendship of fellow adults.

The summer before I turned 19, I was a sophomore, and a bunch of us planned a summer trip to Cape Hatteras. My parents had meant to take a family vacation instead, something we’d never been able to do before. In the end they chose to put it off to the next summer. They were glad I had good friends, and though they were hesitant about this newfangled churchgoing thing I was going for, well, it seemed good for me. (They were all such nice kids!) When I got back a month before school, Dad and I argued about faith and God and whether the Mets were ever going to get back to the Series. We played Axis and Allies until he had to leave for the night shift, and then picked up when he got home. Right after his 42nd birthday, he got a full checkup. The doctor noticed that there were little, faint little lines across his lungs. Dad had been a smoker since he was 16, but he promptly began to work his way out of his pack-a-day habit.

After got home from college we planned to pick right up again: planning for Christmas while arguing some more about God and faith before he went to work. We were amazed the next night when he came back only a couple of hours later, ill enough to vomit in the front yard after pulling up. Dad was never sick. He was certainly never sick enough to actually miss work. He worked through a kidney stone; he only missed a week after his hernia operation. Mom suggested that he go to the hospital, but Dad called it a bad flu and just needed some rest.

It was, in fact, the warning sign for an impending heart attack. Later they told us that it had been so massive that being in the hospital when it happened wouldn’t have made a difference. At the time we didn’t know what it was. He hadn’t complained of the classic chest, arm, or jaw pain, nor did he look clammy or short of breath. When I heard my mother cry for help and ran into the bedroom, I thought that it was a seizure of some sort, until I heard his last breath rattle through him.

For the record – even if you know what you’re doing, CPR does not work on waterbeds.

The church was packed for the funeral. There were people he knew from every job he’d had for twenty years and two states, and clients he’d printed t-shirts for, and neighborhood friends that we hadn’t seen since we’d moved to Jersey. The neighbors with the crushed fence were there – they became friends afterward, leading Dad to joke once that he should have dropped a tree on them the first day. He touched hundreds of people without ever having a byline in a comic or a business empire or a line of action figures. Sixteen and one-half years later, my brother and sister, adults themselves, are getting along with careers and lives of their own. Mom is doing well too.

When I was a boy, I thought that Nights in White Satin was a song about medieval soldiers writing love notes to their fair maidens back home. By the time I was old enough to know better, I’d already inherited his taste for sweeping musical epics, and soundtracks, and some Billy Joel thrown in. I also inherited the joy of imagination, the sense of wonder, and the love of adventure. I even turned out to be a sap who sings along to the radio, though my voice is a baritone. (And Kate, I also like to sing the backup harmonies.) Someday I hope that I prove as dedicated to my family as he was to all of us. And I like to think that I write the kinds of stories that my father would have loved to read.

One of his arguments with me about God was that Heaven couldn’t obey the second law of thermodynamics. What kept it going? It is the same thing that always kept him going – love. It’s what keeps us going now that he’s passed on to where all loves are made perfect. Of course, we normally think this about our loved ones, but for weeks after he died I had dreadful nightmares about him: all darkness, with only the small red glow of the end of his cigarette, and his voice saying, “OK, I’m going to go die now. Have a good night.” And always that last breath. Then I had one last dream – only this one picked up where all the others left off. He went off to die, but woke up the next day (and why not? It was his house); and when I came out of my room and saw him, it wasn’t a surprise, except that he had a Bible. “You know, Mike,” he said, “I think I’m beginning to understand this stuff.”

Since he was the kind of guy who went out of his way to help new folks find their way around, I have no doubt that he’s now introducing himself to Nina’s Dad, showing him around - and wondering if the Mets will ever get back to the Series.

Introductions here take longer than there, which is why this couldn't be something like Avitable’s splendid post-it below. I would prefer not to tie up so much of someone else’s space. The problem is, when someone lives life right they take up a space that can never be filled, no matter how long we type. I miss him as much as ever. That's not something wrong with me.

9 comments:

Great post - absolutely loved it.

Wow. Night Fly is one hell of a writer. Excellent post and I'm sure Nina will be in tears while reading it.

That was lovely. Thank you so much for sharing that.

And my trip down memory lane, Pathmark, Rickel’s Home Center, wow.

I had forgotten about those places.

wow...great post.

I'm happy to have had a chance to glimpse into the life of your wonderful dad. Beautifully written post, a lovely tribute. Thank you :)

Hey, 'Fly, I don't know if I ever said how much I always enjoy it when you write about your dad, so I'm saying it now. This one definitely made "the room get a little dusty," as you term it.

And I think it fulfilled Nina's request nicely.

P.S. Baritone, huh? I can just imagine you singing the "Superman" song by Crash Test Dummies. :)

I'm in tears after reading it.

Lovely, 'Fly.

You're definitely making me miss my Dad.

Great post. And your dad did a bang-up job on The Scorpion knocking Spidey's lights out!

Post a Comment